Then you realize that the ground is getting closer. You barely have time to register that this is going to be bad. And that it's going to hurt.

It is bad. And it hurts.

In late November, I was riding my bike home following the path I do everyday. Part of the journey is a short trail connecting Burnside Road with the back of Tillicum Mall. On this day, dusk, 5:00 pm, water had washed out a pothole that had been filled by gravel back in the summer. Was the washout caused by all the rain we had received in November? Or was it run-off from the watermain that had burst in Tillicum Mall an hour previously? I don't know. All I do know is that as I went down the path, my front wheel caught the pothole and I flipped off my bike. There was a small culvert ahead of me with a concrete pad over top of it. I landed on the concrete pad with all my weight on my left shoulder.

"Ummmfph!"

The air rushed out of my lungs on impact. I bounced off my shoulder and onto my back (my backpack, actually). My legs swung up beside me and ended up in some bushes just off the trail. I'm not sure what happened to my bike. At least it didn't run over me.

I knew right away something was wrong with my left arm. It didn't feel "attached" properly. Still, I tried to gently move it, but the pain toldme that I had probably broken it. There was also the disquieting sensation of things rubbing together that should not be rubbing together.

Okay, so the left arm was clearly an issue. What else was broken? I hadn't hit my head (and yes, I always wear my helmet). I wiggled my toes, they seemed okay. My right arm seemed fine. It felt like I might have a scrarch on my left leg, but this was minor. Everything seemed up and running save my left arm.

I needed my cell phone which was in my backpack, and was now underneath me. Okay. This was gonna hurt, but there wasn't much else to do. Cradlling my left arm as best I could, I swivelled on my butt, getting my legs out of the bushes. Then I sat up.

Yes, it hurt.

I rested a moment, then cradled my left hand in my lap, then slowly unbuckled and removed my backpack.

I somehow managed to get my left arm out of the straps, then I opened it up and fished out my phone. I turned it on, hoping that it still had some juice. It did, I dialed 911. The operator was cool and professional and able to figure out what trail I was on. He asked if I was bleeding; I said I didn't so. He asked if I could get up and walk along the trail. I said I probably could, but I'd just as soon sit where I was.

I hung up and started to call family members to alert them to my plight. I told my mother that Louise would call soon. (I was supposed to help Louise move some furniture that evening -- clearly, I would do anything to get out of that.)

Just as I finished calling my mother, my first guardian of the evening arrived. A gentleman named Ollie rode down the trail and stopped to assist me. He picked up my bike from across the path and offered to wait the ambulance came.

When the ambulance arrived, Ollie, who as it turned out lives just a couple of blocks from me, offered to take my back home.

The bike was fine. Of course.

The paramedics checked me out. They cut away my bike jacket and jersey from my arm. I'm no doctor, but I could see that my shoulder looked wrong. Instead of curving down, it suddenly dropped off, and there was a large bump where there shouldn't be a bump. This was the ball joint at the end of arm sitting in a place where it shouldn't be. They checked my arm for numbness and I had a big numb spot on the outside of left arm. This indicated possible nerve damage.

They immobolized my arm by wrapping what looked like a life preserver around me, they got me to feet and we walked down the path. I climbed into the ambulance and sat down. They moved me over to the stretcher later as they tried to put in an IV line in my right hand. The paramedic kept failing to find a vein and apologised profously for continually poking my right hand in vein, er, vain. We went to Victoria General Hospital.

The one nice thing about being seriously injured is that you go to the front of the queue at Emergency. This was probably a good thing, as by the time the ambulance got me to VGH, my arm was really hurting and I could feel myself getting more uncomfortable. I was probably going into shock, perhaps not deeply, but going there.

As I was waiting to be admitted, one paramedic noted my discomfort and offered me a blanket. Being a stoic male, I declined the offer.

"Let me give you some advice," said the paramedic. "When a paramedic offers you a warm blanket, you should take it."

"Golly," I said, "maybe I'll take that blanket after all!"

It was now about 6:00, about an hour after I fell off my bike.

Soon, I was wheeled into a cubicle, where they quickly started me on an IV. A doctor came in, took a quick look and very quickly determined that at the very least my shoulder was dislocated. He asked if I had any numb patches and I indicated I did, on the side of arm. This could mean nerve damage.

Then he uttered the one word that I was longing to hear: morphine!

But soon I was left alone, and I reflected on my situation. I would need help tending to my sick cat. Someone was going to have to call work and let them know I was going to be off for a few days.

I looked at my arm. Man, I really wrecked it.

By this time, more of my guardians began arriving. First, my sister Brenda arrived, followed by my girlfriend Louise. Each time, the nurse mistook them for my wife.

My memory of events during this period is somewhat fluid, but somewhere between the blood tests and the IV drips, they took me to X-ray.

This was not an experience I'd like to repeat.

The x-rays taken while I was standing up weren't so bad, but I had to lie flat on my back for a set and this really hurt. I never saw any of the "before" X-rays until much later, but lying flat was excrutiating and I could clearly feel bones floating around in there. That was 20 minutes that I never want to repeat.

But interestingly, the numb patch in my arm regained feeling after the x-ray ordeal. I surmise that something moved just enough to take pressure off the nerve, and there were (and are) no more concerns about nerve damage.

I was taken back to my room to await judgement. Brenda and Louise both commented about how cold my hands were.

Soon, a young woman appeared, the orthopedic intern. She'd looked at x-ray, and reported that my arm was broken in three places and my shoulder dislocted. Worse, I had broken ay arm at the ball joint, making repairs all the more troublesome.

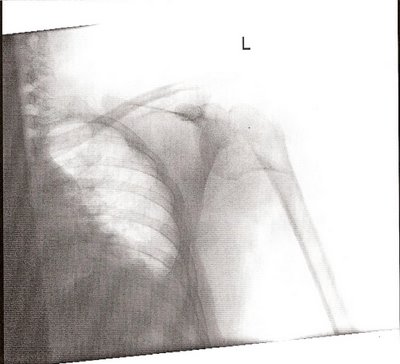

Here's the x-ray:

Now, I'm no doctor, but clearly you can see that the shoulder is out of the socket, and the ball is broken, and not in the correct shape.

She said there were two courses of action. I was going to need surgery on the arm, no question. But do we fix the dislocation with surgery at the same time, or do we fix the disocation manually, then do surgery on the arm later?

This didn't seem like much of a choice to me. If I'm going to go under the knife anyway, must as well do it all in one go.

But she wanted to call in some experts, so who am I to argue?

Somewhere along the way, the paramedic's gear was removed from my arm and replaced with a sling which I am still wearing. (I'm typing this one-handed, so please read this at half your usual reading speed to get the full effect.)

The intern returned with the verdict.

"When I suggested we fix the dislocation first, everyone laughed at me."

There were two problems with her plan. First, the ball was broken off. It was not attched to the rest of the arm. There was no way to re-insert the ball into the socket. It probably would have caused more damage. Secondly, even if it was safe to proceed, she probably couldn't have done it.

I'm a big guy, and she was not a big girl. (She made Chantelle at work look like Shaq.) She physically could not have done it and the last thing my broken arm needed was someone heaving and hauling on my shoulder.

She said she would start on the paperwork and took a felt pen and initialed my injured left shoulder.

So it was surgery, a one-stop fix everything chop. Sort of like Midas Mufflers.

Surgery was set fot 7:45 the next morning, not at VGH, but at Royal Jubilee Hospital. The only question was, could they find a bed for me there? An ambulance was ordered anyway to transfer me. Louise and Brenda said their goodbyes and headed out to spread the word that I would, in fact, live. They noted before they left that my hands were warming up.

A nurse returned with the paperwork for me to sign, but stopped herself before handing it over. It seems that the intern, despite having examined and marked my injured left shoulder, put down on the forms that it was my right shoulder that was to be operated on.

Oops.

Once the paperwork was fixed, I signed. Good thing I'm right-handed.

So there it was. I was facing my first surgery since having my tonsils out when I was 5.

The orthopedic surgeon, my newest guardian, drove over from the Jubilee to examine me. He explained that the surgery would take about two and a half hours. I've heard since that he is the best "shoulder man" on the Island. So far, I'd have to agree.

Around about 11:30, an ambulance arrived to transport me to the Jubilee, they found a bed for me, so we were all set. They loaded me up, and away we went. It was a quiet night for emergencies, the paramedics said. The quietest night they'd ever seen. They'd been on duty for six hours, and I was their first call. And I was just a glorified taxi ride.

By 12:30, I was safely tucked in my bed in Jubilee. Surgery was mere hours away.

"Go towards the light," said the voice.

I could see the light, beckoning, calling.

I have not had any surgery or anesthesia since having my tonsils removed as a child. I have no recollection of being under.

"Go towards the light."

Sometimes things go wrong in surgery. You don't wake up. Could this be happening now? Could the surgery have gone horribly wrong and now I was to find out the answers to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything?

"Go towards the light."

Or was something else happening?

1:15 am.

The nurse comes by and offers me a drink of water. It will be my last drink before surgery. She asks when the last time was that I went to the washroom. It's been hours, so she suggests that I go.

She helps me out of bed, and I stagger along the floor, my busted left arm and shoulder in a sling, my right arm dragging my IV rack. I make it out of my little area, but I have no idea where the washroom is.

"Which way?" I ask.

She points to my left. A door is open, with a light shining behind it.

"Go towards the light."

"A fine thing to say to a person hours before surgery," I harrumph.

"Oh great," she mumbles, "it's going to be one of those nights."

It's amazing how much your life can change in an instant. This morning, I was dreaming of an 18' kayak. Now, after tumbling off my bike, I'm wondering if I can go to the bathroom without screaming.

Kayaking is a distant memory.

There was no screaming. In fact, the entire process was mostly painless. I return to bed, and sleep in fits and starts. I awake around 7, about 45 minutes before surgery. Breakfast arrives for the other patients, but not for me. The nurse warns me that should a breakfast accidentally arrive for me, I shouldn't eat it. I haven't eaten in 18 hours now, but I'm not hungry. In fact, I will go about 30 hours between meals. I was never hungry.

The nurse returns to explain the procedure. Around 7:45, the anesthesiologist will come and sedate me. (This never happens.) They will wheel me into the waiting area, then the operating room. The anesthesiologist will then inject something into my IV and put me out, and from my point of view, I will wake up right away in the recovery room. No time will pass for me. I may be a little disoriented, but it should pass quickly. No dreams.

The anesthesiologist does arrive, with questions for me, plus papers for me to sign. Then an orderly comes and wheels me into PreOp.

I don't give it a lot of thought, but it does occur to me that I may be facing my last conscious moments. Mistakes do happen. Things sometimes go wrong. But I'm resigned to my fate. It's in the lap of the gods.

I'm wheeled into the orthopedic surgical room. The operating table is narrower than I thought it would be and there's some discussion of how to transfer me from my bed to the table. Finally, I say that I will walk over to the table. Someone helps me up and off the bed, and I cross over to the table and lie down.

It hurts, of course. Lying down on my back is the most painful position. Someone calls for "shoulder extensions"; the bed is so narrow that my shoulders hang off the sides, and for my mangled left shoulder, this isn't helping.

I'm not aware that the shoulder extensions ever arrive, and now the anesthesiologist has my attention. He explains that during surgery, they will be freezing the areas they operate on. This will reduce the pain when I come around. I'm all for that.

He starts by poking something between my left shoulder blade and neck. He's trying to find a certain nerve or muscle group, I guess. He wants me to tell him when I feel a tingling like a mild electric shock.

"Feel anything?"

"No."

"Feel anything?"

"No."

"Feel anything?"

"No."

"Feel anything?"

"No. Wait. There's a bit of tingle. By the shoulder blade."

"Okay, good. That tells that I'm in the right area--"

Then I open my eyes.

Which is odd because I do not remember closing them.

But my first sensation is a good one. My left arm, even though it feels sore and swollen, also feels attached and whole again.

I focus on a clock on the wall. It's almost noon. Four hours have passed in a blink.

There's a machine beside me automatically checking my vitals. I can feel it inflating to check my blood pressure.

I glance over at my left arm. I have a long bandage stretching from above my shoulder to half-way down my arm.

A nurse appears. She says everything went well, but the surgery was four hours, not the planned two and a half. They found additional damage in my shoulder to repair. They kept re-locating my shoulder and it kept falling out. So in addition to screws and a plate in my arm, they also performed a Bankart Repair. This is a procedure that ties a strip of muscle across the joint to hold the arm in place in the shoulder socket. I don't know it at the time, but this will slow down my recovery, and probaly permanently decrease my range of motion.

The nurse leaves as she tries to find a bed for me; they did the surgery even though they did not have a room to put me in afterwards.

What else did they do to me? They put in a plate and screws to fix my arm. They repaired a small break in the shoulder socket; unfortunately it was where some tendons and ligaments were attached so they had to be repaired. Also, a lot of muscle had to be re-attached as it had come away from the bone. Here's what my shoulder looks like now:

Yes, the plate and pins are permanent. I will never have an MRI and I will beep at airports.

The nurse returns, they found a bed for me. I ask for a drink of water. My throat is killing me -- it's raw from the breathing tube they had down it.

I'm wheeled to my room, pumped full of antibiotics and morphine. I'm tired and I feel like sleeping, yet I also don't want to sleep. Mostly, I just sit dazed, occasionally nodding off.

Karl will visit me around 5:00 PM -- I spent more of his visit asleep than awake. Others will visit me. Louise, Brenda, my niece Kai all stop by. Paula and Bernie visit. For some perverse reason, Bernie is mostly concerned that my right hand still works. Paula thinks I look like I've been hit in the face with a sledge hammer. Not that there's anything wrong with my face, but because the shock of this life-altering moment is still sinking in.

Dinner arrives around the same time Karl does. It's a fish patty thing, which wasn't very good. The mashed potatoes are excellent. The nurse tells me to go easy -- it's my first meal in 30 hours. I nibble at it.

Details are a blur, but I am constantly poked, prodded and checked by nurses. Everything seems to be normal.

I'm sharing my room with three other patients. Across from me is a young guy who's here for the long haul. He's just ordered a tv. He knows all the nurses by their first names. They are asking him for advice on his course of treatment. I'm guessing dialysis.

Beside me is an old lady. I'm never sure what is wrong with her, but she seems to have all sorts of ailments. She is constantly being taken out for tests.

The third roommate is an older man who's left left hand got into a fight with a table saw. I give the victory to the man only because all his fingers are still attached.

Afternoon fades into evening, and into night. It's early in the morning now. And I need to pee. There's no nurse around, so I slowly sit up. My back is killing me. I carefully stand and walk to the washroom, dragging my IV rack. A nurse has already helped me do this a couple of times, so I already got the hang of it. When I return, I stop at the window and look out. I can't see much -- most of the view is blocked by the roof of another part of the hospital. But I can see the tops of some trees, some streetlights, and clouds.

I miss being outside.

And it will be along time before life becomes normal again.

I carefully climb back into bed.

Sleep eludes me.

In the morning, I go down for x-rays. It is there that I see for the first time the steel and pins that are now part of my arm.

Holy jeez. I'm bionic or something.

The rest of thr day is a blur. More drugs, more pills. More blood tests. They want me out -- they need the bed. In mid-afternoon, I get the word. I can go home.

My long recovery begins.